Research Highlight - Ichthyosaur Flipper Fossil Reveals Ancient Stealth Technology

A team of paleontologists has uncovered evidence that a massive Jurassic marine reptile, Temnodontosaurus, evolved a form of “stealth mode” to silently hunt prey in dimly lit seas 183 million years ago. The study, published in Nature, centers on a remarkably preserved one-meter-long front flipper from Germany’s Toarcian Posidonia Shale.

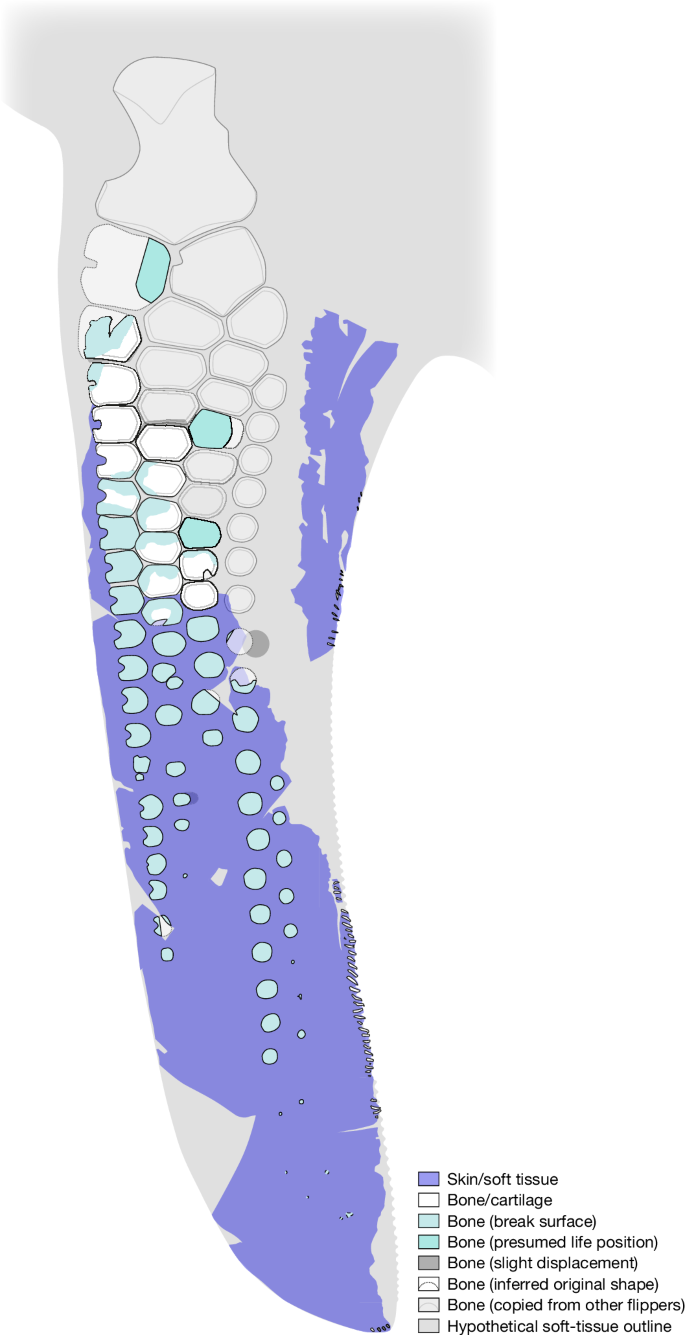

The fossil reveals extraordinary soft-tissue structures: a wing-like flipper outline, fine parallel skin ridges and a flexible tip, all suggesting aerodynamic finesse. Most strikingly, the trailing edge of the flipper features unique cartilage-based structures called chondroderms, unlike anything previously known in fossil marine reptiles. These elements, embedded within the skin, likely reduced hydrodynamic noise during swimming.

Fig. Skeletal reconstruction and hypothetical soft-tissue outline

Using computational fluid dynamics, researchers showed that these adaptations suppressed low-frequency sound, allowing the visually guided Temnodontosaurus with eyes the size of dinner plates to approach prey undetected. The fossil also reveals high aspect ratio flippers, a trait linked to lift-efficient, gliding motion seen in modern whales.

This discovery documents exceptional soft-tissue preservation; introduces a new anatomical structure; combines morphology with biomechanical modeling; and offers a novel ecological hypothesis—stealth predation in marine reptiles. It even has implications for modern bio-inspired design, like quieter underwater vehicles.

By illuminating how extinct predators fine-tuned their bodies for silent hunting, the study reshapes our understanding of Mesozoic marine ecosystems and shows that stealth isn’t just for submarines.

——

Reference

Lindgren, J., Lomax, D.R., Szász, RZ. et al. Adaptations for stealth in the wing-like flippers of a large ichthyosaur. Nature (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09271-w

File Download: